Major advances in spine surgery — from minimally invasive techniques to complex spinal deformity procedures — have opened the door for a much wider group of patients to receive care. Through a multidisciplinary collaboration of specialists in neurosurgery, orthopaedics and physiatry, the UCLA Spine Center is optimizing the care of patients who might not have been eligible for spinal surgery in the past.

“We can decrease their medication use after surgery and get them back to work quicker, and the outcome is often better.”

Minimally invasive spinal surgery has become an increasingly important part of the armamentarium, says Langston Holly, MD, co-director of the UCLA Spine Center. Minimally invasive spine surgery was initially developed for patients with degenerative disc disease, but over time techniques have evolved for patients with other spinal pathologies, including tumors and trauma. “Just as general surgery took large, open procedures and turned them into laparoscopic procedures with fewer complications and shorter hospital stays and recovery times, we have been able to do that with spine surgery,” Dr. Holly says. Often, patients are able to go home within a few hours after a surgery that would have previously required one or more nights in the hospital.

Dr. Holly notes that the minimally invasive approach is particularly important for spine patients because many have been on pain medications and may be more sensitive to postoperative pain. “We can decrease their medication use after surgery and get them back to work quicker, and the outcome is often better,” he says. Another benefit of the minimally invasive approach is that it allows the surgeon to preserve supporting structures and maintain the integrity of the spine, reducing the chances of the patient needing additional surgery at a later time.

The UCLA Spine Center also includes expertise in highly complex adult and pediatric spinal deformities. “The quality-of-life impact that adult spinal deformity and degenerative conditions of the spine have on patients is huge, and it is underappreciated,” says Andrew Vivas, MD, assistant professor of neurosurgery.

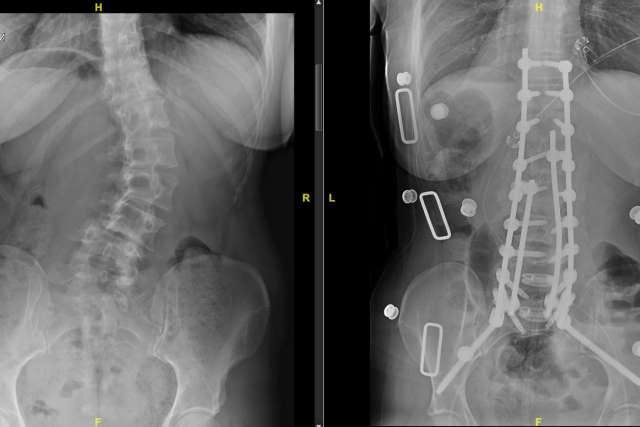

The surgeries performed by Dr. Vivas and his colleagues have a low margin for error. Historically, Dr. Vivas notes, spinal-deformity corrections had unacceptably high rates of complications, including paralysis, and so the surgeries were mostly avoided. But over the past three decades, the technology has greatly improved — in particular, the ability to closely follow the function of the spinal cord during surgery through intraoperative neuromonitoring and a variety of minimally invasive techniques used to augment the deformity surgery. “These are challenging cases, but if we’re able to do these surgeries safely and with low perioperative morbidity and rates of complication, we can dramatically improve patients’ quality of life, with significant improvements in pain, selfimage scores, patient satisfaction, mental health scores and overall function,” Dr. Vivas says.

The significant advances in safety and outcomes have changed the eligibility calculus, to the point that large-scale spinal-deformity surgery is being performed on many patients well into their 70s and 80s, Dr. Vivas notes. Dr. Vivas also performs a substantial number of revision spine surgeries, another highly specialized procedure for patients who have in many cases suffered for years with their spines fused in a painful position. As with the other procedures, successful surgery requires the type of multidisciplinary approach featured at the UCLA Spine Center.