A novel UCLA Health study is seeking to modify a particular brain circuit that appears over-sensitized in people who experience chronic symptoms after a concussion.

an assistant professor in neurology at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine and , said the study is testing personalized brain stimulation to reset a brain circuit that may be overactive in people who don’t fully recover within weeks after a concussion.

Maladaptation of the circuit, which can be seen on an MRI, may be preventing the brain from eliminating fears about returning fully to pre-injury levels of activity and resolving symptoms, he said. As a result, people avoid certain everyday activities that may trigger headaches, dizziness, sensitivity to light, brain fog and depression or anxiety.

“It is important as a public health concern to lessen the burden and cost of chronic concussion symptoms,” said Dr. Bickart, who is principal investigator. “It’s been hard to even diagnose, let alone find targets for treatment of this condition.”

Dr. Bickart’s team of researchers are targeting the circuit through non-invasive brain stimulation. They are also asking participants to play a very personal role in the research by discussing their deepest fears about how their symptoms could interfere with their hopes and dreams.

Participants then listen to recordings of themselves contemplating their worries before the brain stimulation in order to further activate and target the circuit that may be responsible for their lingering symptoms.

“It’s actually become to me one of the most interesting and potentially rewarding parts of the experience,” Dr. Bickart said, noting that, for some people, the recording can serve as a form of exposure therapy that helps neutralize their fears. “My hope is that when combining stimulation with the recording, participants will re-engage more fully in the activities they enjoy most, and in their lives overall.”

Study background

In 2022, the Department of Defense awarded a $3 million grant to UCLA Health for a four-year study in adults using short courses of brain stimulation. In the largest clinical trial of its kind, researchers administer four-minute courses of a magnetic pulse, called transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS. Some participants receive placebo, or sham, stimulation.

TMS can activate or inhibit nerve cells and larger circuits in the brain, and has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for tinnitus, some psychiatric conditions and certain types of migraine headaches.

So far, 10 study participants have enrolled, with half of them finishing the four-month protocol of 10 brain stimulation sessions and four follow-up MRIs. The study will recruit up to 90 people.

Dr. Bickart said the treatment could potentially help the 30% to 50% of people who still have debilitating symptoms more than three months after a concussion, despite no observable injury on a brain scan.

One potential cause of lasting symptoms could be a phenomenon known as fear avoidance, where people refrain from activities or situations that could trigger symptoms.

Avoiding exercise, using a computer, or going outside into bright sunlight can be protective in the short run.

“In the long run, it can actually cause intolerance, sensitivities, and deconditioning,” Dr. Bickart said. “Ultimately, avoidance seems to worsen symptoms and even bring about new symptoms for some people.”

A circuit to target

The study is testing that theory by seeking to modify and reset the brain circuit that may have become overactive and oversensitive after the concussion.

MRIs are able to detect a blood flow pattern indicating an overactive connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, which regulates emotions. This overactivity could be an indication of a maladaptation that is preventing the brain from eliminating fears and resolving symptoms.

“We get an MRI on everyone at baseline to map their whole brain and find that one circuit,” Dr. Bickart said.

Researchers are using TMS to disrupt the overactivity of the circuit, which could then help with fear extinction and enhance coping ability, Dr. Bickart said.

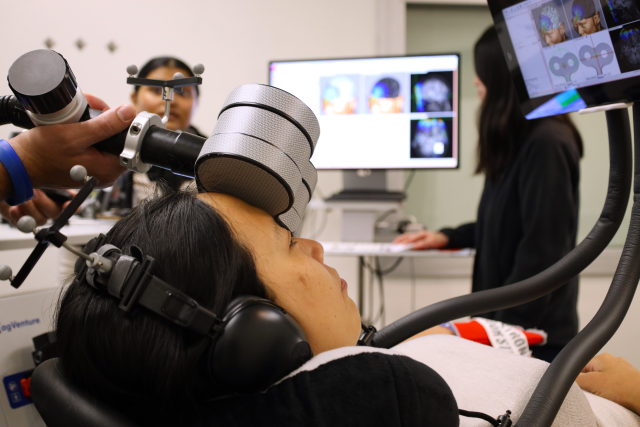

The brain stimulation is delivered through an electromagnetic coil placed on the participant’s forehead. Researchers position the coil based on individualized targets generated by a Bay Area company from each person’s MRI. The area of the brain receiving stimulation is roughly the size of a quarter.

“We navigate in real time, as if it was neurosurgery, on the computer screen that’s showing us where we are physically in the brain,” Dr. Bickart said.

When receiving brain stimulation, participants do not require sedation. They may feel a buzzing sensation and muscle contractions in their forehead or eyebrow. They can view the same images of their brain on tablets that the researchers are using to position the coil for the treatment.

Study participants will receive either active brain stimulation or placebo stimulation. Most will listen to a recording of their own voice talking about activities they fear will trigger symptoms. A smaller group will listen to a script about a neutral activity.

For a fear-based script, Dr. Bickart said if a participant experiences migraines after exercising, the person may decide to stop working out.

“In doing so, they become more sensitive to physical exertion,” he said. “Even with less intense exercise, they provoke a migraine.”

The person’s script could include how lack of exercise might lead to a host of negative consequences, from weight gain to heart disease and diabetes. From there, negative thoughts could spiral to feelings of intense failure and loss of one’s dreams.

In comparison, the neutral script is about the steps to prepare a sandwich.

Study participants listen to the recordings before treatment and reflect on them during the brain stimulation to help keep active the circuit that researchers are aiming to target.

“They’re continuing to think through the trauma recording and the worst-case scenario if their symptoms never went away,” Dr. Bickart said.

Results could help improve treatment

The researchers do not know who is receiving actual brain stimulation and who is receiving the placebo. Dr. Bickart said participants are wearing Oura smart rings, a device that continuously monitors sleep, vital signs and physical activity. They are also answering questions about their symptoms and performing cognitive tests.

“In general, everyone seems to be tolerating the protocol very well,” he said. “We don’t know if one arm of the project is doing better than the other. What we do know is the data is coming through with high quality.”

Dr. Bickart said his team has been providing regular updates to the Department of Defense.

Mild traumatic brain injury, which includes concussion, is relatively common among members of the military. It occurs through similar mechanisms to civilians, such as motor vehicle accidents or physical trauma.

Dr. Bickart said he’s hopeful the research can result in better treatment and outcomes. The trial is open to people 18 to 65 who experienced a concussion or mild traumatic brain injury three to 12 months ago and have lingering symptoms.

“Right now, there’s no FDA-approved therapy for concussion,” Dr. Bickart said. “It causes return visits to the hospital or missed work and stress to the family. People have been very excited to join the trial and participate.”