In 1990, a global consortium of researchers embarked on one of the most ambitious scientific endeavors in history. The goal of the was to determine the exact order of 3 billion bases, the building blocks that make up our DNA.

Mapping this sequence was a painstaking effort. It took 13 years and about $3 billion for scientists to determine 92% of the human genome. But it required for full completion. Technology needed to catch up.

Now, advanced sequencing techniques not only determine genetic profiles down to the level of a single cell, but can be processed in mere hours. They have become powerful tools in biological research.

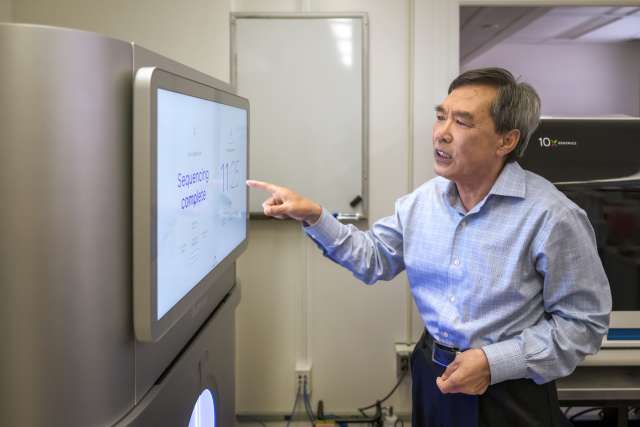

“If you want to do life science research, genomic data is essential,” said Xinmin Li, PhD, a professor in the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “These technologies (allow us) to study interactions and collective functions of individual genes within the whole genome.”

Researchers studying anything from tropical plants to transgenic mice to treatment-resistant tumors can turn to the Technology Center for Genomics Bioinformatics. As a hub for genomics services, TCGB performs next-generation sequencing and analyzes results using complex technologies.

To avoid burning money on costly equipment, researchers across the country outsource to TCGB. Last year, it served 272 labs at UCLA and 63 outside institutions, including universities and pharmaceutical companies. It is also one of six shared resources at the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Our mission is to provide the best technologies, support investigators comprehensively and help them advance science,” said Dr. Li, the center’s founder and director since 2007.

Three ways to sequence

TCGB is spread across interconnected rooms where its 20 scientists in long, powder-blue lab coats work in shifts to run the center for 12 hours a day, seven days a week. When a researcher submits a sample, TCGB will assess its quality, and then use one of three methods to determine its genomic code.

Bulk sequencing, developed a decade ago, is least refined. It crushes the sample, sequences an aggregate of different types of cells and produces an average profile of their gene expression. Bulk comprises about 40% of the sequencing in TCGB.

“It’s simple, cost-effective and mature technology,” said Dr. Li. “It can help you get from nowhere to somewhere very quickly to generate a hypothesis.”

Another 40% is single-cell sequencing. It’s used when a more specific profile is needed, such as studying an individual tumor cell’s signaling or mutations. This technology was developed about seven years ago.

“But in single-cell, you need to disassociate the cells and you don't have a structure anymore,” said Dr. Li. “Cells (exist) in a highly structured organization that enables each cell to function correctly and efficiently, and enables the cells to communicate.”

Spatial sequencing, just three years old, allows single-cell resolution while retaining this structure. Dr. Li predicts it will become the dominant genomics tool in the next few years.

Melanoma research

Spatial was the sequencing of choice for Nataly Naser Al Deen, PhD.

“Bulk sequencing is like a smoothie,” she said. “You know the contents of it but you don’t know where in that smoothie they are located. Spatial is like a fruit salad. You know this piece of apple is next to this piece of orange, neighboring a piece of kiwi.

“So (with spatial), you know what cell types are there, which ones are closer to or interacting with each other, and what kind of cell state are they in.”

Dr. Naser Al Deen is a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of UCLA Health JCCC member Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, which is investigating an immunotherapy treatment for melanoma. Sequencing allowed them to compare biopsies from treatment-resistant tumors, as well as tissue from patients who responded to the treatment.

“We processed 68 samples (with TCGB) from August until January,” said Dr. Naser Al Deen. “We booked both machines with two teams running our samples back to back. And they were very accommodating because they knew how important it is to understand the primary resistance or what’s unique about these tumors.”

The samples came from biopsies from patients and were 5 microns in thickness (by comparison, a human hair is about 75 microns across). But even with that miniscule sample, the spatial sequencing technology could capture up to 18,000 genes, while preserving the sample’s structure in space.

“The customer’s sample is very precious,” said Hyunju Lim, PhD, TCGB’s lab manager and associate director at the UCLA Health JCCC Genomics Shared Resource. “We know that it’s not possible to get another clinical sample, so we have one shot and have to get it right.”

Expensive technology

Throughout TCGB are the powerful machines processing these samples. The center purchased six spatial platforms for about $1 million. Three single-cell platforms run more than $600,000. And the five bulk sequencers total about $3 million. Add in additional costs for essentials such as reagents, consumables and software licensing, and sequencing is an expensive laboratory method.

But TCGB keeps the fees charged to users competitive because of the high volume of requests.

High costs of technology are not the only reason why researchers outsource sequencing to TCGB. It is also a highly specialized skill. Staff train for three years, and each is proficient with all the procedures and technologies to ensure the smooth completion of a customer’s request.

“We’re all trained uniformly so we can hand off tasks and handle the pressure of so many requests,” said YooJin Lee, a staff research associate at TCGB. “There is a lot of repetition in the technology, but I challenge myself to be more efficient every time.

“Plus, every sample is unique. I’ve seen whale skin, dragonfly wings in a tube, bees, spiders, and different types of plants.”

Analyzing the data

Many universities and pharmaceutical companies also have genomics centers. What distinguishes TCGB is what follows after sequencing.

“Genomic data is complex,” said Dr. Li. “It’s an enormous amount of data and there’s specific software required to analyze it.

“Word or Excel are not going to work,” he joked.

Rather than handing off raw data, staff scientists employ powerful bioinformatics tools to analyze the layers of data that are produced by sequencing. The data are also analyzed with the researcher’s experiment in mind.

“We always ask what their biological question is,” continued Dr. Li, “So that when we analyze, we deliver targeted results that can help them answer that question.”