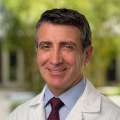

Photo: Drew Moghanaki, center, with Dr. Jane Yanagawa, and former NFL player Chris Draft, promote the White Ribbon Project lung cancer awareness campaign. (Photo by Joshua Sudock/UCLA Health)

‘This is about trying to get to a time when no one dies of lung cancer,’ says Dr. Drew Moghanaki, chief of thoracic oncology for UCLA Health.

Drew Moghanaki, MD, MPH, is on a mission to dismantle three major stereotypes about lung cancer: that it’s a smoker’s disease, that it isn’t curable and that surgery offers the only chance for survival.

He describes lung cancer as “America’s silent epidemic” — a malignancy that kills more people than the next three cancers combined. About 230,000 people are diagnosed every year.

“Our work is about trying to get to a time when no one dies of lung cancer,” says Dr. Moghanaki, a professor and chief of thoracic oncology in UCLA Health’s department of radiation oncology and member of the . “If we catch it early, we can save people’s lives. And by that, I mean we can cure four out of five people whenever lung cancer is caught early.”

Lung cancer doesn’t just affect smokers

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 10% to 20% of lung cancer cases — 20,000 to 40,000 each year — occur in .

Anti-smoking campaigns emphasize the connection between smoking and lung cancer, which has created social stigma against people with the disease, Dr. Moghanaki says.

“We teach kids that smoking is bad because smoking can cause lung cancer,” he says. “While this is an important thing to teach kids, the message has unintended consequences. It leads people to think that smokers are bad people, and therefore people with lung cancer are bad people.”

There are problems with this oversimplified approach, he says.

First, it inextricably connects lung cancer with smoking, which fails to account for the tens of thousands of diagnoses made in people who never smoked, or who used to smoke and quit a long time ago.

Second, it puts the onus for the disease on individuals who smoked, without acknowledging the deliberately addictive nature of cigarettes.

And third, it leads to a marginalization of people with lung cancer, that they somehow created their own circumstances and deserve the consequences, Dr. Moghanaki says.

“We physicians are also guilty for contributing to this stigma,” he says “We have been labeling people who smoke as ‘smokers’ for years in almost all of our communications with each other.”

White Ribbon Project

A former UCLA Health medical resident and his wife launched an effort in 2020 to change perceptions about people with lung cancer. Pierre Onda, MD, an internist who completed his residency at UCLA, and his wife, Heidi Nafman-Onda, created the after she was diagnosed with lung cancer.

A health educator and fitness trainer who also graduated from UCLA, Nafman-Onda never smoked, yet was diagnosed with stage 3 adenocarcinoma of the lung in 2018.

Frustrated that national campaigns implied lung cancer stems only from smoking, the Colorado couple made a white ribbon out of plywood in their garage to encourage greater awareness of the disease.

Dr. Moghanaki and UCLA Health were early supporters of the project, which has distributed more than 1,000 white ribbons to date across the U.S. and Canada, and as far away as Germany, the Netherlands and the Philippines.

Scores of UCLA Health patients with lung cancer, as well as physicians, have been photographed with the white ribbon this year to support the awareness-raising effort.

Treating lung cancer

For patients with early-stage lung cancer, there are now two promising treatments that offer a chance for cure, Dr. Moghanaki says. One is surgical resection and the other is radiation therapy. Scientists are learning which of these treatments is better for any given patient, he says, although surgery is generally preferred by most lung cancer specialists. This preference is largely because of tradition, he says, since radiation techniques weren’t sophisticated enough to target the tumor with enough dose until fairly recently.

To figure out when surgery or radiation therapy might be a better option today for a patient with early-stage lung cancer, Dr. Moghanaki is leading the Veterans Affairs Lung Cancer Surgery or Stereotactic Radiotherapy study — the largest clinical trial in the U.S. that is comparing these two treatments.

The VALOR study is sponsored by the VA Cooperative Studies program and enrolling 670 patients to study the effectiveness of radiation therapy as an alternative to surgery for early-stage lung cancer.

Radiation oncology research over the past 25 years has led to new approaches to treating early-stage lung cancer, Dr. Moghanaki says. Rather than providing daily, low-dose treatments over four to six weeks, patients with early-stage disease now have the option to be treated in just a few consecutive days with radiation therapy.

“No one could have predicted how well stereotactic radiation therapy would work,” Dr. Moghanaki says. “It’s 95 to 97% effective at controlling the cancer from ever growing again in that area.”

The VALOR study compares this radiation therapy to traditional surgery in patients who have been diagnosed with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer that has not yet spread and would otherwise be offered a standard surgical resection for their tumor.

Dr. Moghanaki believes that the results of the VALOR trial may show that stereotactic radiation therapy is a better treatment than surgery.

“One of the promising things about radiation therapy as a potentially preferred upfront treatment option for early-stage lung cancer is that it doesn’t require any surgical incisions and therefore might not perturb cancer cells that may have already spread before treatment,” he says. “In about one in five patients, even when we operate on them, the cancer has already spread and will eventually show up elsewhere in their body. We have good scientific evidence that the surgical insult to the chest and the body can stir up those other cancer cells to grow more quickly.”

This might be because the post-operative healing process leads to a lot of inflammation, Dr. Moghanaki says.

“Meanwhile, evidence shows radiation therapy often actually down-regulates inflammation,” he says.

Another emerging treatment approach is immunotherapy, Dr. Moghanaki says, adding that UCLA Health will soon launch a clinical trial offering immunotherapy treatment for early-stage lung cancer.

Changing the future of lung cancer

With increased awareness of how stigma around lung cancer impacts patients’ lives and promising research and treatment developments, Dr. Moghanaki is optimistic about a future in which lung cancer is caught early and most people with the disease go on to live long lives.

A lot has changed in recent years, he says.

“We really have to shine a light of hope on lung cancer,” he says. “This is because it wasn’t that long ago when we didn’t have good treatment options for patients.

“With poor survival rates, national campaigns such as those led by the American Cancer Society focused primarily on getting people to stop smoking,” he says. “While this was important and was highly effective in lowering the incidence of lung cancer, it shifted much-needed attention away from remembering that no one deserves to get lung cancer and that we need more research to better understand how to prevent and treat lung cancer in people who smoked a lot, a little, or none at all.”

But there was an inflection point in lung cancer therapies in recent years, Dr. Moghanaki says.

Doctors started to see their patients with lung cancer living longer, he says, which has brought much-needed optimism to the entire cancer community.

Learn more about lung cancer services at UCLA Health.