Debra Ball was losing faith.

Battling metastatic breast cancer since 2016, Ball was advised by her doctors to “get her affairs in order” and start hospice care at the end of 2023. Meanwhile, Ball’s 97-year-old mother needed help after her part-time caretaker resigned.

During this time, Ball met regularly with , an interfaith chaplain at the , for spiritual and emotional support while processing her frustrations and worries.

“I was just in an absolute panic,” says Ball, 67. “I told Mark I was angry at God. I was angry at Jesus, like, ‘Why are you doing this? What is the purpose? I don’t understand.’”

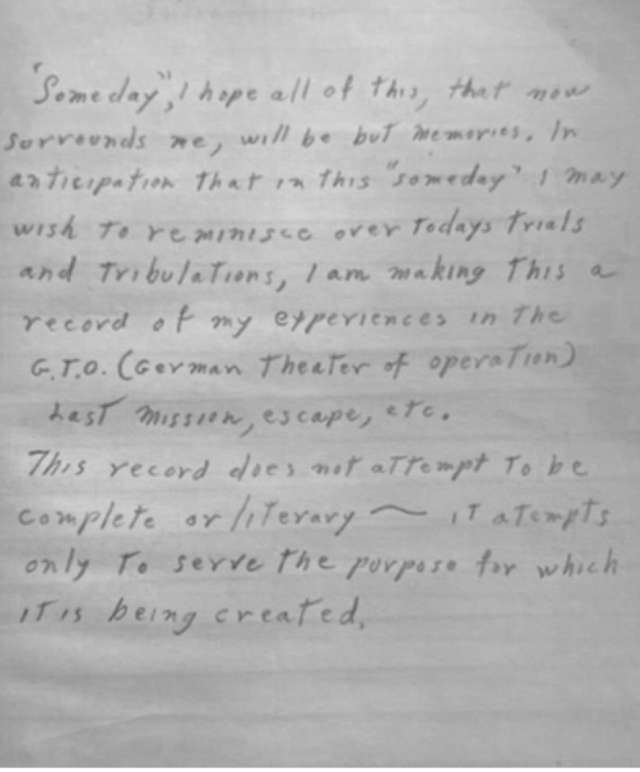

Around the same time, Ball’s mother had misplaced one of Ball’s most prized possessions: a diary her father, Seymour Rodheim, kept while a prisoner of war in World War II. Rodheim served as a bombardier for the U.S. Army Air Force.

Ball was just a child in 1966 when her dad died of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The handwritten diary was her only tangible reminder of him. She would thumb through it every Father’s Day, looking at the pictures he’d drawn of the prison facility, the barn where he sometimes slept, and the planes he’d flown before being shot down over Germany. He never talked about the war when Ball was a child. This diary was how she connected with that part of his life. And now it was lost.

Her visits with Buchanan were a comfort to Ball as the challenges mounted.

Yet the diary, her mother’s care and Ball’s own health were about to be restored through a series of serendipitous events.

First serendipity

Desperate to find someone to help look after her mother, Ball posted on Facebook that she needed a “grandmother’s helper” to handle light housekeeping and food preparation a few days a week. She was surprised to get a response from Kim Weggeland Sperr, a woman she’d known since their now-adult sons were in elementary school. Sperr offered to volunteer her time. She was happy to help out with grocery shopping and doctor’s visits.

“Kim started coming over and she kept hearing us talk about this diary,” Ball says. “And she said, ‘You know, my brother is the commissioner of the board of the National World War II Museum.’”

Shortly after that conversation, Ball discovered her dad’s diary crammed into a folder with other papers her mom had collected.

Sperr was curious to see this 80-year-old document.

Sperr came to Ball’s home to look it over and asked if she could tell her brother about it. She took photos of a few of the diary’s pages and texted them to him. He immediately shared those images with the CEO of the museum, who said, “We have to have that. This is historical.”

Next thing Ball knew, she was on the phone with Sperr’s brother, Ted Weggeland. He told her the museum had plenty of boots, uniforms, medals, guns, Jeeps, tanks and aircraft. What they needed more of, he said, were personal accounts like her father’s diary.

Not only did the diary offer a personal perspective on the experiences of an American prisoner of war, but it was written by a Jewish soldier whose religious identity was unknown by his German captors.

Ted asked if Ball would consider donating the diary to the museum in New Orleans.

Protecting a legacy

She talked it over with her mom and sister. “It was really emotional for us,” Ball says. “This is what we have left of daddy.”

Weggeland understood the emotion involved, Ball says. What about loaning the diary to the museum, he offered, to be photographed and returned?

But Ball felt it would be appropriate to donate it outright. The diary was already disintegrating with time. She feared it would eventually become “confetti” in a forgotten box somewhere. But if the museum kept it, it would be protected, and could continue to educate people about the war for generations to come.

She decided to let the National World War II Museum have the diary as a way of protecting her father’s legacy.

“Now he can live forever,” Ball says. “Because when I was 9, I always thought I didn’t do enough to keep him alive – which still makes me cry, because I know that comes from a child’s heart. But it’s still the same feeling in a 67-year-old’s heart.”

Until donating the diary, Ball hadn’t realized how many unresolved feelings she had around her father’s death, and how largely he still loomed in her life.

In her conversations with Buchanan at the Simms/Mann Center she talked about “how serendipitous this whole process has been,” he recalls.

“This was a kind of confirmation that her life has had fulfillment both spiritually and relationally,” Buchanan says.

Everything for a reason

Had her mother’s caretaker not resigned, Ball wouldn’t have reconnected with Sperr and learned that her brother was a leader of the World War II Museum. If she hadn’t met Weggeland, the family’s precious diary wouldn’t have found a permanent home.

“It just proved to me very solidly that you don’t know what God has set before you,” Ball says. “That you just have to go on pure blind faith. You may not know the answers. You may not understand the why. But there are reasons things happen.”

Because her doctors had told her to get her affairs in order, Ball prayed to stay alive long enough to get the diary into the hands of museum curators. Now, her tumors are shrinking, she says, her hair has grown back, and she has the satisfaction of knowing her dad’s legacy is protected.

“What brings me comfort about the whole thing, the way I like to think about it,” Ball says, “is at night, when the museum closes at 5 pm, that the spirit from all of these men and all of their articles can come out and be together.”

Adds Buchanan: “This has been a legacy project for her in the best way. It’s really given her purpose and meaning.”