This is the second of two parts. Part I appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of U Magazine.

When Dr. Eduard Pernkopf completed the first installment of his seven-volume Topographische Anatomie des Menschen (Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy) in 1937, the discovery of penicillin was several years away, and Jonas Salk was a third-year medical student, 15 years from developing the vaccine that would eradicate polio. Imaging techniques that are common today — ultrasound, CT, MRI — were, if they were considered at all, merely science fiction speculation.

And yet, well into our current century, what was known simply as the “Pernkopf atlas” continued to be regarded as the preeminent resource of its kind. Mapping the human form down to the most minute detail through exquisite hand-drawn illustrations, the atlas was acknowledged as a masterpiece of both science and artistry. But the horrific nature of the authors and their methods had now become clear: Dr. Pernkopf, an Austrian anatomist who served as dean of the University of Vienna’s medical school while overseeing the atlas’ creation, was an avowed Nazi, as were the artists he employed. Many of the bodies portrayed on the atlas’ pages were victims of Nazi terror, their executions often timed for when Dr. Pernkopf’s team needed more subjects.

Even as circulation of the original volumes waned once the abhorrent details came into focus through a series of revelations in the 1980s and 1990s, their influence persisted. “For many years, Pernkopf was to anatomy what Bach was to music,” says Kalyanam Shivkumar, MD (FEL ’99), PhD (’00), director of the UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center. “Everything after Pernkopf was a version of Pernkopf.”

Part one of this story chronicled how Dr. Shivkumar (“Shiv” to those who know him), an internationally renowned electrophysiologist and leading innovator of heart interventions, became deeply disturbed upon learning that the premier anatomic atlas for the types of nerve procedures he wanted to develop carried such a vile origin story. Unable to let go of his revulsion, Dr. Shivkumar decided to embark on a decade-long effort, with his UCLA colleagues, to surpass what many had deemed unsurpassable — rendering Dr. Pernkopf’s work obsolete through a series of original anatomic atlases and making them available to colleagues around the world via online, open-access publishing.

Part two of our story touches on both that journey and its evolution into something greater: Amara Yad (a combination of Sanskrit and Hebrew translating to “the immortal hand”), an initiative aiming to restore the sanctity of the doctor/patient relationship through education and actions that address historic transgressions.

“There’s an old saying, ‘the eyes cannot see what the mind does not know.’ Without an atlas, you can’t interpret. Imaging data won’t become knowledge, and knowledge won’t become wisdom without proper interpretation.” Dr. Kalyanam Shivkumar

Anatomy is the oldest clinical discipline, dating back to at least the third century B.C., and it continues to serve as the starting point in the education of first-year medical students. But as medicine advanced at breakneck speed in the latter part of the 20th century, some questioned its relevance to clinical practice.

“During medical school, I was told time and again by professors that anatomy was a dead science,” recalls Jamil Aboulhosn, MD ’99 (RES ’02, FEL ’05, ’06), director of the Ahmanson/UCLA Adult Congenital Heart Disease Center. “They said if you wanted to rise in academic medicine, you had to go subcellular, to DNA and RNA — that everything about anatomy was already known. What’s funny is that about a decade after that, it became clear that anatomy was still at the center of medical innovation and advancement.”

As a pathologist who subspecializes in cardiovascular diseases, Michael Fishbein, MD (RES ’75), has always relied on anatomy for his work. But many specialists had little use for the discipline, he notes, until advances in imaging led to the rapid growth of interventional procedures among cardiologists, radiologists and others — necessitating a detailed and nuanced grasp of anatomy for diagnosis, interpretation of images and minimally invasive treatments. “All of a sudden, everyone wants to come and see hearts,” muses Dr. Fishbein, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Pathology and Medicine. “If, rather than opening up the chest, they can go in through the vessels, they have to know where they’re going and how to get there.”

An anatomic atlas, be it the ill-gotten set of volumes produced by Dr. Pernkopf or the one Dr. Shivkumar and his team set out to replace them with, provides a road map to be studied prior to heart procedures that rely on catheter-based techniques involving the coronary arteries and veins, or that target the cardiovascular nervous system. In Dr. Shivkumar’s world, which involves treating patients with complex, life-threatening arrhythmias, knowing every nook and cranny makes all the difference. When performing a catheter-based treatment on a young person with an abnormal rhythm in a sensitive region of the heart, missing the target by a few millimeters can result in the patient needing a pacemaker for life.

And on that score, high-tech imaging doesn’t replace the anatomic road map. “There’s an old saying, ‘The eyes cannot see what the mind does not know,’” Dr. Shivkumar says. “Without an atlas, you can’t interpret. Imaging data won’t become knowledge, and knowledge won’t become wisdom without proper interpretation. Human anatomy isn’t going to change, but our understanding of it gets better.”

When Dr. Shivkumar told anatomists of his intention to create a map of the human heart that would render the Pernkopf atlas and its derivatives moot, he encountered heavy skepticism. With their arresting images and painstaking detail, the volumes created by Dr. Pernkopf and his group were considered unbeatable. Even Dr. Shivkumar, for all his confidence, recognized the daunting task. “It was like climbing a mountain,” he says.

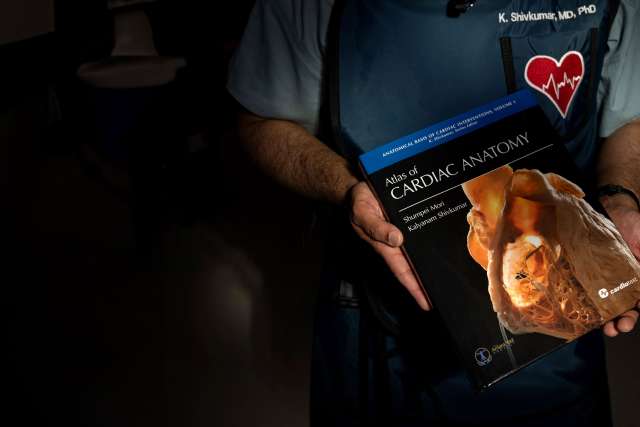

Dr. Shivkumar never doubted that he could assemble the expertise. As his co-author on the first of seven planned volumes of Atlas of Cardiac Anatomy, he recruited Shumpei Mori, MD, PhD, a physician-scientist who specializes in cardiac anatomy and advanced clinical imaging at the UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center. Over the course of the next decade, more than a dozen faculty and trainees would devote significant time to climbing the mountain.

One of the major challenges to producing a comprehensive resource on cardiac anatomy is the need to acquire a sufficient supply of specimens — the donated hearts of deceased patients — to capture the organ’s variations. For certain structures, understanding all of the possibilities can require dissecting a couple hundred organs. Dr. Pernkopf faced no such challenge, relying on his connections with the Nazi regime for procurement. At UCLA, specimens were ethically obtained from a variety of sources, including OneLegacy, the nation’s largest organ-procurement organization, which provided donor hearts unsuitable for transplantation; the National Institutes of Health, which also helped to fund the work; and the UCLA Donated Body Program.

Foundational to the effort was Dr. Shivkumar’s acquisition and digitization of approximately 4,000 slides that had been languishing in the basement of the Cleveland Clinic Library — detailed images taken by the late cardiac surgeon Wallace A. McAlpine, MD, for an anatomic atlas of the heart published in 1975. While that work had provided great utility for its time, an update was needed. “Dr. McAlpine’s atlas was published when the major treatment was open-heart surgery,” says Peter Hanna, MD (FEL ’21, ’23), PhD ’21, a UCLA cardiac electrophysiologist who contributed to the new atlas. “The field of interventional cardiac electrophysiology didn’t exist.”

Today, the diagnosis and treatment of heart rhythm disorders typically involves the placement of catheters and the delivery of radiofrequency energy to modify the heart’s architecture. “The first goal is always to do no harm,” Dr. Hanna says. “And because we don’t have direct visualization like a cardiac surgeon would, we have to know where we are when looking at an image.”

Beyond making use of Dr. McAlpine’s photography, the group headed by Drs. Shivkumar and Mori replicated his “perfusion-fixation” technique. Upon obtaining a donor heart — often in response to a call that came in the middle of the night, from a hospital two or more hours away — it was crucial to preserve its three-dimensional structure; this required inserting plastic tubes hooked to a pump to maintain pressure perfusion for 24 hours in a cold room.

“Our atlas is clinical cardiac anatomy by cardiologists, which makes it different from textbooks of basic cardiac anatomy written by anatomists.” Dr. Shumpei Mori

Once the heart was “fixed,” it was brought to a photography studio set up by Dr. Mori. With the heart mounted on a tripod atop a rotational table and illuminated by six adjustable LED light sources, Dr. Mori used a digital SLR camera with a 200-millimeter lens to systematically photograph the organ in various anatomic positions to create the undistorted versions featured in the atlas. Dissections were made depending on which chamber of the heart and which interventional procedure was to be covered.

“To show the progressive dissection with GIF clips, we needed to dissect the heart without changing its position on the tripod, and at every stage of the dissection we needed to capture the images,” Dr. Mori explains. “This process of preparation, dissection and recording required patience, meticulousness, precision and time.”

While he was outwardly confident in his team’s ability to render the Pernkopf Atlas moot, Dr. Shivkumar admits harboring some initial concerns. “In the first year or two, it seemed very daunting,” he says. But as his group approached the midway point of the 10-year undertaking, “I knew Pernkopf could be beaten.”

Atlas of Cardiac Anatomy: Anatomical Basis of Cardiac Interventions, Volume 1, published in September 2022, features more than 200 full-color photographs of the human heart and its adjacent structures meant to serve as a foundational study of cardiac anatomy and a guide for those caring for patients with heart disease. In addition to the original high-resolution images and the previously unpublished, restored works from the McAlpine collection, the atlas includes 25 anaglyphs — three-dimensional images viewable with 3D glasses.

One of the recognized strengths of the Pernkopf atlas was its detailed display of the peripheral nervous system — over the years, nerve surgeons were particularly reliant on the images for their complex operations. But the first volume of the UCLA atlas provides a tour through parts of the anatomy Dr. Pernkopf’s group couldn’t have envisioned would bear fruit. The enhanced images establish new road maps not only for electrophysiologists like Dr. Shivkumar and his colleagues, but also for neurosurgeons, thoracic surgeons, pain-management experts and others. In the book’s foreword, Francis E. Marchlinski, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, and William G. Stevenson, MD, of Vanderbilt, describe viewing anatomic structures heretofore shown as silhouettes on fluoroscopic imaging: “It is like having the lights turned on in a dark, yet familiar room.”

“Our atlas is clinical cardiac anatomy by cardiologists, which makes it different from textbooks of basic cardiac anatomy written by anatomists,” Dr. Mori explains. “Anatomic atlases, including Pernkopf’s, are often shown using illustrations or with collapsed hearts that distort the cardiac anatomy. By showing the structural anatomy in far more detail and captured from clinically relevant directions, then sharing it without paywalls, our atlas can ensure safe and effective procedures for patients around the world.”

Dr. Fishbein, the UCLA cardiovascular and pulmonary pathologist who assisted in the anatomic studies, has seen his share of atlases. “None go into the detail, and have such beautiful images, as this one,” he says. Dr. Fishbein’s participation was personal as well as professional: His parents and sister were Holocaust survivors, and he was born after World War II in Belgium, where they had gone into hiding.

For Dr. Shivkumar, the technical superiority of Atlas of Cardiac Anatomy over the Pernkopf atlas tells only part of the story. “Our atlas comes from people who have seen humans suffer and have helped to make lives better,” he says. “Pernkopf’s came from Nazi murderers.”

By the time his group was set to publish the first volume, Dr. Shivkumar was entertaining a broader vision. He began to engage in conversations with his friend and colleague Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, MD (RES ’90, ’92, FEL ’95). A professor in the Division of Cardiology and co-director of the UCLA Evolutionary Medicine Program, she also holds a master’s degree in the history of science and co-authored The New York Times bestseller Zoobiquity: The Astonishing Connection Between Human and Animal Health.

“I was moved by Shiv’s sense of outrage that a physician, the head of a major medical school, was abusing trust,” Dr. Natterson-Horowitz recalls. “More than almost any physician I know, Shiv is driven by purpose — here to remove this moral stain. As we had more conversations, I saw that Amara Yad could extend beyond correcting just this one terrible event in the history of medicine.”

In early 2022, Drs. Shivkumar and Natterson-Horowitz began building out their vision for Amara Yad as a campuswide initiative, based in the UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center, that would honor the victims of medical exploitation through corrective action.

The first goal: extending the work inspired by the Pernkopf-era atrocities. Amara Yad intends to publish a series of anatomic atlases — free to all in support of medicine’s life-saving mission. Volume 1 of the Atlas of Cardiac Anatomy lays the foundation for the cardiac atlases set to follow in rapid succession. The spring 2024 release of the series’ second volume, Atlas of Interventional Electrophysiology: Correlative Anatomy, by Drs. Shivkumar, Mori and Roderick Tung of the University of Arizona Health Sciences, serves as an anatomic guide for the treatment of complex arrhythmias. Future volumes will bring in other authors from UCLA and beyond to cover structural heart disease, imaging, cardiac surgery, cardiac neuroanatomy and congenital heart problems.

But the heart is just the beginning. “In science we say function follows form,” Dr. Shivkumar says. “We are entering an era in which many fields of medicine are going to be revolutionized by modulating nerves. Mapping the wires that connect various parts of the body — the nervous system — will have an impact on all of medicine.”

To complete the volumes of what Dr. Shivkumar calls “the internet of the human body,” Amara Yad is inviting collaborations with experts from multiple universities, supported by private and extramural funders. The Amara Yad Challenge, to be held in summer 2024, will bring in representatives from several medical schools to discuss the need and the task ahead. “This should be a multi-university, multinational effort to build on this portal of knowledge,” Dr. Shivkumar says.

Amara Yad's broader vision stems from the reality that the evils associated with the Pernkopf atlas are by no means isolated chapters in the annals of the medical profession.

During the Holocaust, physicians were enlisted to conduct medical experiments on unwilling victims in concentration camps and to develop race-based health policies, including mass sterilization of people viewed as “lesser” humans. Prior to the systematic murder of Jews, doctors and nurses were complicit in Aktion T4, the Nazis’ “euthanasia” program, in which an estimated 250,000 individuals with psychiatric, neurological or physical disabilities were put to death to “cleanse” the Aryan race; German psychiatrists were charged with signing the papers that consigned institutionalized persons to death.

And the American medical community has committed shameful acts of its own. Perhaps the most notorious was the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. From 1932 to 1972, the U.S. Public Health Service, in a study designed to learn more about the effects of untreated syphilis, allowed 400 Black men to unknowingly go without care. “The history of medicine, both distant and recent, includes too many instances in which the absence of a moral view led to catastrophic consequences, and those violations have carry-over effects,” Dr. Natterson-Horowitz says. “To optimize health, patients must believe their physician is always looking out for their best interests. When the sanctity of that relationship is breached by anyone, it affects all of us.”

Numerous studies have shown that the legacy of Tuskegee and other injustices — including more recent evidence indicating, for example, that Black patients are undertreated for pain and that LGBTQ+ patients continue to report significant levels of discrimination from providers — is a high level of distrust that too often results in avoidance of needed care. Breaches in trust can also undermine advice issued by physicians and public health authorities. The anti-vaccine movement was catalyzed by a widely publicized 1998 study by the former physician and discredited British academic Andrew Wakefield and colleagues, published in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet, that purported to show a link between the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine and autism. Although the authors were later found to have committed a series of ethical transgressions and misrepresented their results, leading the journal to fully retract the paper in 2010, the study — whose findings were never replicated — continues to be cited by vaccine skeptics.

Amara Yad plans to use such acts of medical immorality as both educational tools and inspiration to bring about moral correctives, just as the Pernkopf atlas has provided fuel for the unprecedented endeavor to produce an open-access anatomic map of the human body for the benefit of patients around the world. While the contours of that model remain under construction, a key component will involve educating students at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. That will include a rotation in which students learn from medical ethicists and historians about the sacred nature of the physician/patient bond and cases in which it was violated, as well as participating in reparative research, education and community-outreach projects.

At the Medical University of Vienna, where Dr. Eduard Pernkopf served as dean — dressing in full Nazi regalia and commanding his faculty to swear an oath of loyalty to Adolph Hitler — the sordid history serves as a cautionary tale for today’s medical students. They learn about the Pernkopf history both in anatomy class and on a visit to the Josephinum, the medical history museum located on the university campus, which displays the original Pernkopf atlas drawings and proofs, along with accounts of the unpleasant truths behind them.

“More than almost any physician I know, Shiv is driven by purpose — here to remove this moral stain.” Dr. Barbara Natterson-Horowitz

Juxtaposed with the Pernkopf works, the Josephinum houses a large collection of three-dimensional Italian wax anatomic models dating to the museum’s origins in 1785 under Joseph II of Austria, Holy Roman Emperor. “Our students can see the anatomy drawings with swastikas on them and learn about the darkest times of medicine and humanity, then learn by walking through the most beautiful art pieces from the past,” says Christiane Druml, the UNESCO Chair of Bioethics at the Medical University of Vienna, who also serves as director of the Josephinum.

The Medical University of Vienna has embraced Amara Yad, its leadership having visited UCLA and consulted with Dr. Shivkumar. “Today’s doctors face so many time constraints that their ability to talk with colleagues and superiors about ethical issues is often limited,” Druml says. “But it’s important that they not only learn about the past, but also discuss the many new issues that come up in an era of rapid change, such as artificial intelligence and genome editing.”

As technology continues to usher in possibilities that were once unthinkable, ethical questions are being raised that couldn’t have been fathomed during the time of Dr. Pernkopf. “Physicians have much more power today,” says Rabbi Michael Berenbaum, a professor at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles and one of many experts Dr. Shivkumar has consulted for Amara Yad. “We need to remind everyone that people who think only of science without considering the ethical consequences of the knowledge they gain bring shame to the profession.”

Under Dr. Shivkumar’s leadership, the UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center has earned an international reputation for excellence. Its innovations in the treatment of abnormal heart rhythms have saved countless lives, drawing cardiologists from around the world to learn the techniques. But Dr. Shivkumar believes Amara Yad has the potential to be the center’s most important contribution. “The foundation of medicine is ethics,” he says. “Without it, nothing else matters.”

Dan Gordon is a frequent contributor to U Magazine. His two-part story, “UCLA In the Time of AIDS,” received the Robert G. Fenley Gold Award for Excellence in Writing and “Best of Show” from the Association of American Medical Colleges.