A research team led by , director of the , has discovered that restoring glutathione—a key antioxidant that prevents cell damage—rejuvenates old muscle stem cells. Muscle stem cells are activated to help repair damaged tissues after injury, so finding a way to make old muscle stem cells behave like young muscle stem cells could help improve the body’s ability to recover from injury when we get older.

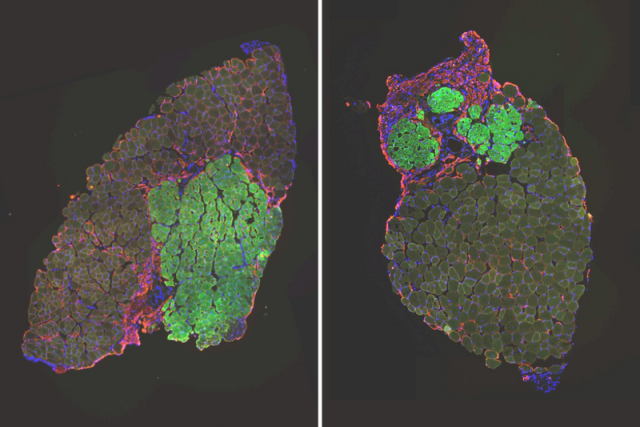

The study found that with age, muscle stem cells in mice evolve from one population of cells into two distinct subpopulations of cells that differ in their glutathione metabolism. The cell population with high levels of glutathione are good at muscle repair while the population with low levels of the antioxidant do a poor job.

Young mice start off with one population of uniform muscle stem cells that is highly effective at muscle repair. With age, in addition to having a population of old stem cells that still behave like young cells, they acquire a second population of stem cells that is less effective at repairing muscle.

The research group identified glutathione metabolism as the main driver of this movement into two cell groups, paving the path toward a potential therapy that would prevent old impaired stem cells from ever developing in the first place.

“If all stem cells could be kept functionally young, maintaining tissue regeneration across the lifespan would be feasible,” said Rando, who is also a professor of neurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology in the UCLA College.

The findings are in the peer-reviewed journal Cell Metabolism.

By giving the muscle stem cell population with low levels of glutathione a drug that makes more glutathione, the research team was able to rescue these old impaired cells and make them more effective at repairing muscle. To prove that low glutathione levels is one culprit of the negative impacts of aging on health, the researchers also successfully made the young cells behave like the impaired old cells by depleting them of glutathione.

It has long been known that tissue repairs less effectively and less quickly as we age. However, pinpointing what happens in our bodies that makes it more difficult to heal from a bone fracture or recover from a skin or muscle injury in our 70s than in our 20s has been a challenge.

“Here, we’re honing in on glutathione metabolism as one driver of what goes wrong as we get older,” Rando said. “By testing drugs and other methods to restore glutathione, we are one step closer to developing therapies that enable old tissues to repair as well as young tissues.”

This research was funded by the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs and by training awards from the Stanford University School of Medicine, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging.