The bad news kept coming after Melanie Shatner Gretsch’s breast cancer diagnosis a couple of years ago. Her cancer turned out to be aggressive, and it had spread far enough that a cure might not be possible.

“Up to that point, every time a doctor spoke to me, things were worse,” she said, recently. “It was very scary.”

UCLA Health breast surgical oncologist , said Gretsch’s case was very nuanced because although the cancer had spread to lymph nodes in her chest, it was still potentially curable – it had not gone far and had not reached any vital organs.

“It’s two different treatment pathways if you are treating breast cancer that has not spread versus breast cancer that has spread or metastasized,” Dr. Thompson said. “Technically, Melanie was stage 4, but we felt like she was one of those rare cases of stage 4 breast cancer that was curable.”

Over nearly 18 grueling months, Gretsch underwent every available treatment at UCLA Health, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, surgery and radiation.

“Dr. Thompson says I did the maximum,” she said. “There is no more they could have thrown at me.”

Now cancer-free, Gretsch is writing a memoir about how she experienced emotional healing while recovering, a project that she hopes will help others.

“I really look forward to giving back to other people that are afraid and going through it,” she said.

A tiny bump

Gretsch, a 60-year-old married mother of two daughters in college, had always been on top of her breast health.

Starting at 40, she underwent annual mammograms with ultrasound because she had dense breasts, which can make it harder to see tumors on breast imaging.

In July of 2022, Gretsch, who lives in Sherman Oaks, felt a small bump on her left breast in the middle of the night. It seemed like a bug bite, but still she called the next day and booked a same-day imaging appointment. Her last screening had been in February.

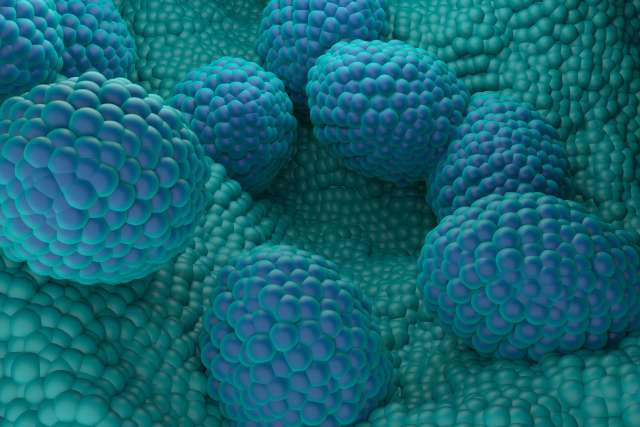

She underwent a biopsy that revealed breast cancer. She later learned that her tumor was HER2-positive, meaning it contained extra copies of a gene that causes cancer cells to grow quickly.

A friend recommended UCLA Health oncologist . Gretsch wanted to move quickly to complete the work and begin treatment.

“I just felt the immediacy,” she said. “I didn’t know at the time but that was kind of life saving for me.”

In addition to Drs. Glaspy and Thompson, her UCLA Health team included Joanne Weidhaas, MD, PhD, a radiation oncologist. All three are members of the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Gretsch took comfort in UCLA Health’s long history of pioneering treatment for HER2-positive breast cancer. UCLA Health's , also a member of the Cancer Center, led a team that developed , the first gene-based drug for cancer. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1998 for HER2-positive breast cancer and works by blocking receptors on the cancer cells to slow or stop their growth.

According to the American Cancer Society, about 15% to 20% of breast tumors are HER2-positive.

Aggressive treatment

Although Gretsch’s cancer had initially appeared localized, a PET scan found that the cancer had spread to lymph nodes in her chest, which unlike in her armpit, could not be surgically removed.

“I wouldn’t Google anything, but other people would and I could tell when. They looked very concerned,” Gretsch said.

She said the cancer’s spread jeopardized the original plan for her to have surgery after chemotherapy.

“Once the cancer cells spread outside of the breast and immediate surrounding lymph nodes, we can’t remove those cells with surgery and we can’t really adequately treat them with radiation. It also can be a sign of a bigger, harder to treat problem.” said Dr. Thompson, an assistant professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

However, she said Gretsch’s care team unanimously decided that the cancer in her chest was close enough to the original tumor that she could be curable with a broad spectrum of treatment.

“Melanie is special for so many reasons,” Dr. Thompson said. “She really had the lengthiest and most invasive treatment that a patient can go through. We had to be particularly aggressive about her treatment.”

She started chemotherapy in late July 2022, along with infusions of Herceptin and Perjeta, another HER2-positive targeted therapy.

With time, she learned to manage the side effects of chemo and subsequent treatments.

“You are both nauseous and starving at the same time,” she said. “You know you need to eat and you’re shaking because you need to eat and yet everything tastes like vomit.”

In December 2022, she underwent a double mastectomy performed by Dr. Thompson. Gretsch opted not to have reconstructive surgery, with her age and happy marriage factoring into her decision.

Gretsch responded to chemotherapy and targeted therapy well enough that she could have undergone a breast-conserving lumpectomy, Dr. Thompson said, but Gretsch felt most comfortable removing all of her breast tissue, which eliminated the need for future mammograms.

“I felt like I had so much physical trauma that I wanted to take the least traumatic route that had the least amount of things to follow up on,” she said.

Although she doesn’t regret her choice, she said she feels wistful seeing photos of herself before surgery.

“I don’t love that I have no breasts,” she said. “I don’t love that when getting dressed it’s always a consideration of what it looks like on me. It does feel like it takes some femininity away. It makes me sad sometimes, but I’m really glad to be alive.”

After surgery, Gretsch said the lymph nodes removed from her arm pit were all clear and her left breast contained only a residual speck of cancer.

“Dr. Thompson said, ‘This tells me your outlook is excellent,’” Gretsch recalled. “I’ll never forget her emphasis on the word excellent. Then I saw Dr. Glaspy. Honestly, that was the first time we’d seen him smile.”

In February 2023, Gretsch began 25 rounds of radiation plus five extra for the chest lymph nodes. She continued with the targeted HER-2 therapies.

For her, that was the toughest treatment because she’d always sought to limit radiation, even dental X-rays.

“It was emotionally really hard. I can’t believe I’m actively taking this on every single day,” she said. “Your skin gets so burned.”

After radiation, she started another course of chemotherapy that ended in December 2023.

Gretsch said her UCLA Health doctors provided her with extraordinary medical care and nurturing.

“You are in a child/parent relationship regardless of your age,” she said. “You need them to take care of you and you need to trust them.”

She is taking estrogen-blocking medication for five years as a precaution, since her cancer was found to be slightly sensitive to hormone-fueled growth. Her most recent PET scan, in March, found no evidence of cancer.

“For now, we can say that she is cured,” Dr. Thompson said. “The chance of the cancer coming back in Melanie is probably a little bit higher just because she had those cells that got out initially. However, she had a phenomenal response to the treatment and we are all very, very hopeful that this means a long-term cure for her.”

A new chapter

The end of cancer treatment brought a new vulnerability for Gretsch.

“The emotional journey is really intense but I don’t think it fully starts until you finish treatment,” she said. “When you’re in treatment, there’s a safety to it. It was so much attention on the problem. Even when you feel scared, your whole life is geared toward this.”

Writing the book has been therapeutic.

“For me it’s about healing the fears that we have about dying and making peace with it and finally learning to live in the moment,” Gretsch said.

Dr. Thompson, who has read parts of her draft, said Gretsch maintained a beautiful outlook throughout her treatment and has a lot to share with others about what she went through.

“There’s a lot of educational value in that, but also patients knowing they’re not alone in these experiences,” she said. “I think cancer treatment can be very isolating.”

Gretsch sees a physical therapist to regain full range of motion in her left arm after experiencing tightness from surgery and radiation. She hikes or walks most days.

“I do feel well,” she said. “I feel pretty strong, like pretty much myself.”