Pheochromocytoma

Find your care

We deliver effective, minimally invasive treatments in a caring environment. Call to connect with an expert in endocrine surgery.

What is a Pheochromocytoma?

Pheochromocytoma is a rare and potentially dangerous tumor that affects approximately 1 in 500,000 people. The average age of people affected by pheochromocytoma is 50, and it affects men and women in equal numbers. We now know that about half of patients with patients with pheochromocytoma possess a germline mutation (a mutation that can be passed on to one’s children) that is the underlying cause of the tumor.

Pheochromocytomas secrete catecholamines, such as epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). These are vasoactive compounds, that is, hormones that can affect blood pressure, heart rate, and contractility (how strongly the heart pumps) within seconds. Everyone who has been on a roller coaster or gotten up to speak in front of an audience has experienced a surge of adrenaline: a pounding feeling in the chest, a cold sweat, and the hairs on the back of your neck standing on end. Pheochromocytomas do this and much more, often driving blood pressure up to dangerous levels that cause headaches, heart attacks, strokes, and possibly heart failure. Sadly, a fair number of pheochromocytomas are discovered only at autopsy.

Catecholamines are metabolized (broken down) within the body into compounds called metanephrine and normetanephrine. The most accurate way to diagnose pheochromocytoma is by measuring blood or urine levels of metanephrines. Blood tests for pheochromocytoma (plasma free metanephrines) are sensitive but at least 15% of results are false-positive. For this reason, urine testing (24-hour urine collection) is likely the best way to diagnose pheochromocytoma, with abnormal results being levels more than twofold the upper limit of normal. Metanephrine levels between one and two times the upper limit of normal are common in patients with hypertension (high blood pressure) and generally do not indicate the presence of pheochromocytoma. Because pheochromocytoma is considered to be a “ticking time bomb,” surgery is usually recommended. Surgical removal can almost always be performed using an endoscopic (minimally invasive or laparoscopic) approach, resulting in rapid recovery.

Before surgery, patients are prescribed alpha blockers (a class of blood pressure-lowering medications) for several weeks to bring the blood pressure down to safe levels for surgery. Not only is choosing a highly specialized surgeon paramount for the treatment of this rare and risky condition, but also having a specialized anesthesiologist is essential. During these operations, touching the tumor even gently can trigger catecholamine release and a surge in blood pressure. In these cases, the communication between surgeon and anesthesiologist is critical to success.

Pheochromocytoma Symptoms

- Severe headaches

- Palpitations

- Rapid heart rate

- Sweating

- Flushing

- Chest pain

- Abdominal pain

- Nervousness

- Irritability

The most common symptom of pheochromocytoma is hypertension (high blood pressure). Patients can have persistent/chronic high blood pressure, or high blood pressure only during episodes/attacks. A common clinical feature of pheochromocytomas is an attack of symptoms (listed above) that may be frequent but occur at irregular intervals (sporadic). These attacks may worsen in severity, duration and frequency as the tumor grows. Some patients have attacks brought on by physical or emotional stress, while others are awakened from sleep with symptoms.

Pheochromocytoma Causes

Pheochromocytomas develop in specialized cells called chromaffin cells. Located in the center of the adrenal gland, chromaffin cells release adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) which control your body’s blood pressure and heart rate. Adrenaline and noradrenaline trigger your body’s response to a perceived threat, causing your blood pressure and heart rate to increase. A pheochromocytoma leads to an excessive amount of these hormones being released.

Pheochromocytoma Risk Factors

Pheochromocytoma may occur as either a single tumor or as multiple growths. Less than 10% of pheochromocytomas are malignant (cancerous), with the potential to metastasize (spread to other parts of the body). These tumors can appear at any age but are more commonly seen in early to mid-adulthood.

Certain rare inherited disorders have an increased risk of pheochromocytoma. These genetic conditions include Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2 (MEN 2), Von Hippel-Lindau disease, Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), and Hereditary paraganglioma syndromes.

I Have High Blood Pressure; How Do I Know Whether I Have a Pheochromocytoma?

Most people who have high blood pressure don’t have an adrenal tumor. Talk to your doctor if you are having difficulty controlling your high blood pressure with current treatment, if your high blood pressure begins to worsen, if you have a family history of pheochromocytoma or history of a related genetic disorder (MEN2, von-Hippel-Lindau disease, NF1 or hereditary paraganglioma syndromes.

I Have an adrenal nodule; How Do I Know Whether I Have a Pheochromocytoma?

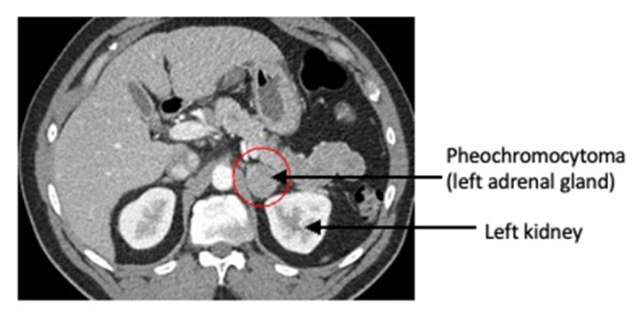

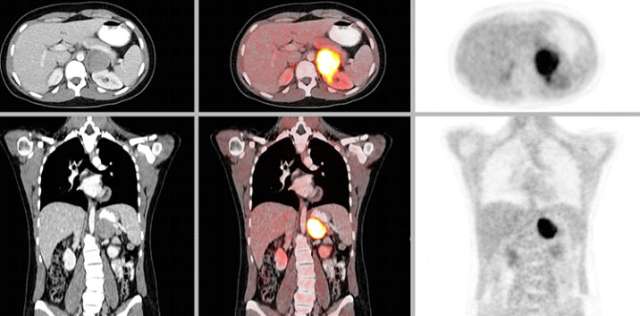

Anyone with an adrenal nodule discovered on imaging (e.g. a CT scan or MRI of the abdomen) should have appropriate biochemical work-up to determine if the adrenal nodule is producing excessive hormones. This is done by laboratory testing of the blood and/or urine. Pheochromocytomas have specific imaging characteristics that can be evaluated on CT or MRI.

How Do You Detect Pheochromocytoma?

The main test to identify a pheochromocytoma is checking the 24 hour urine or blood levels of metanephrines (metabolites of adrenaline). These levels should be at least 2-fold above the upper limit of normal; otherwise, they are likely to represent a false positive finding (i.e. the test is elevated but the patient does not have a pheochromocytoma). Many conditions and medications can cause a false-positive elevation of metanephrines, including Tylenol, anti-depressants, and certain blood pressure medications.

CT or MRI of the abdomen will almost always identify a pheochromocytoma. Additional specialized imaging such as MIBG (meta-iodobenzylguanidine) or Ga-68 Dotatate PET/CT scan can help to confirm a pheochromocytoma and identify multiple tumors or metastatic spread.

How is Pheochromocytoma Treated?

Pheochromocytomas are treated with surgery to remove the adrenal gland that contains the tumor.

A medication called an alpha blocker is given for about 2 weeks prior to surgery to stabilize the patient’s vital signs and get their blood pressure and heart rate under control. This step limits serious complications during surgery, as manipulation of the tumor can cause release of hormones that can raise the blood pressure and heart rate. Having an experienced surgeon and anesthesiologist team is critical for a safe and successful surgery.

After surgery, patients’ vital signs are closely monitored and hormone levels are tested every year to make sure the pheochromocytoma does not recur (come back). Most patients are cured with surgery as long as the pheochromocytoma is completely removed without any break of the tumor capsule during surgery. Pheochromocytomas are usually not cancerous. In the rare cases of malignant pheochromocytoma, treatment options include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRT). Pheochromocytoma treatment.

What Should I Expect After Surgery?

Patients with hypertension prior to surgery often have rapid and significant improvement immediately after surgery. Patients often worry that removing an adrenal gland means their quality of life will be affected or they will need to be on hormone replacement after surgery. But that is not the case. The other adrenal gland produces all of the hormones that the body needs, and hormone replacement is not needed after adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma.

For patients who have non-cancerous tumors that are removed with surgery, more than 90% are doing well with no recurrence after 5 years. Tumors come back in less than 10% of patients, most often in cases where the tumor was malignant or the capsule of the tumor was broken during surgery. Those cases require multi-disciplinary treatment at a specialized center for medical management of blood pressure and symptoms, possible reoperation, and other treatment options previously mentioned.