Case: Breast Imaging in Female Transgender (Male-to-Female) Patients

By: Jason Ni M.D. and Nooshin Najmi M.D.

Introduction:

The term transgender refers to individuals whose gender identity differs from their assigned sex at birth. These patients often undergo gender-affirming hormone treatment surgeries which helps align their physical appearance with their gender identity. With the advent of hormone treatments, transgender women (i.e. male-to-female patients) begin to develop breast tissue and are subsequently at increased risk for both benign and malignant breast lesions. In 2016, there was an estimate of 8 million to 25 million transgender individuals globally and 1-1.4 million transgender individuals in the United States. As of 2022, that estimate is to be around 1.6 million in the United States (1). Given the growing population of transgender individuals in the United States it is important to understand their evolving medical concerns.

In this brief review, we will discuss a case of a benign breast lesion in a female transgender patient and briefly discuss breast lesions in female transgender patients. We will also review current up to date screening guidelines for transgender female patients.

Case:

A 25-year-old transgender woman (preferred pronouns she/her/hers) presented to her primary care provider to establish care. During this visit she mentioned that she discovered a lump in her right breast a few months ago. Physical exam revealed a sub-centimeter right breast mass between the upper outer and lower outer quadrants. There are no associated skin or nipple changes. No palpable axillary adenopathy. The left breast is normal.

Of note, this patient began hormone blockers at the age of 14 and started estrogen therapy at the age of 16. She began using a histrelin acetate implant (a gonadotropin releasing hormone analog; SUPPRELIN) at the age of 14 but is currently not on any antiandrogen treatment. She was initially started on an estradiol transdermal patch (Vivelle-Dot) at the age of 16 and has since switched to weekly estradiol valerate (Delestrogen) injections.

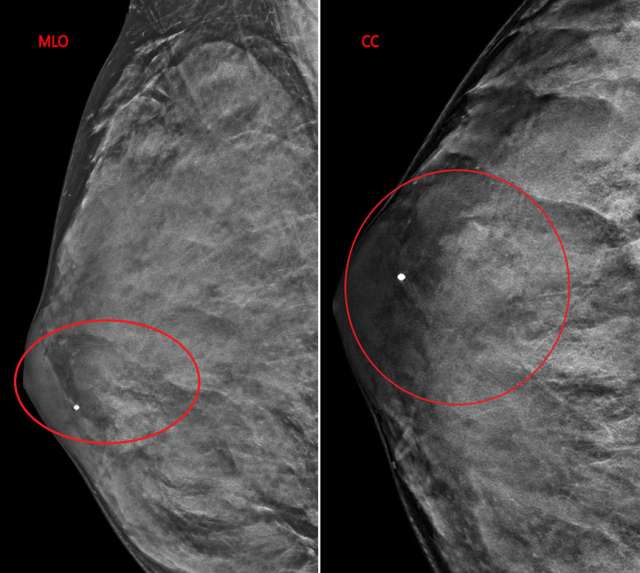

The patient underwent a diagnostic mammogram which revealed extremely dense breasts and an oval mass with circumscribed and obscured margins seen in the right breast at 9 o’clock at anterior depth (Figure 1). Targeted sonographic images were subsequently obtained which revealed a hypoechoic vascular oval mass with circumscribed margins measuring 24 x 10 x 34 mm seen in the right breast at 9 o'clock located 3 centimeters from the nipple (Figure 2). Given the patient’s medical history these findings were given BIRADS-4A and an ultrasound biopsy was recommended.

Successful ultrasound guided core needle biopsy was performed and pathology revealed a fibroepithelial lesion consistent with benign fibroadenoma. There was no evidence of atypia or malignancy.

Physiological Changes:

Given the increase in transgender females and the use of hormonal therapies in these patients, it is important to recognize the accompanying physiological changes that arise from these therapies. Physiological changes are expected after the initiation of hormonal treatments and it is important for radiologists to recognize and distinguish between expected physiologic changes and pathologic changes in transgender females.

Hormonal changes seen on mammography vary greatly. Initial development of the breast bud occurs shortly after hormonal therapy (around the first 3-6 months), however maximum growth varies according to the individual and usually occurs 2-3 years after the start of hormone therapy (2). This may also be influenced on the age of initiation and the adolescent stage of the patient. In this regard, a range of breast density levels are seen mammographically similar to biological females. Interestingly enough, no correlation has been discovered between the density of breast tissue and estrogen levels, or the regimen of gender-affirming hormones administered in transgender women (3).

The supplementation of estrogen lowers endogenous testosterone concentrations by activating the negative feedback loop on the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadal axis. Natural estrogens are preferred over conjugated and synthetic estrogens because it is not possible to monitor the concentration of the latter via blood tests. Testosterone concentrations decrease to low ranges in these male-to-female patients (200-300ng/dL), however many of them will also require the addition of an antiandrogen medication to inhibit testosterone production or block the androgen receptor to reach desired effects (4).

Histologically, transgender women who take hormonal therapy develop breast tissue comprising of breast ducts, lobules, and acini, similar to that of biological women. In contrast, gynecomastia does not have these manifestations and instead only demonstrates ductal and stromal hyperplasia. It should be noted that for this reason, gynecomastia should not be used when reporting breast tissue in transgender individuals for this very reason (1).

As mentioned above, because hormonally induced breast tissue development in transgender women is similar to biological women, it is not uncommon to see similar benign breast findings in these women. In addition to our case described above, there have been case reports of fibroadenomas, cysts, and pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia described in the literature (1).

Hormone Therapy and Breast cancer Risk

In addition to benign lesions, malignant lesions have also been found in transgender women undergoing hormone therapy. Similar to biological women, there have been reports of invasive ductal carcinoma, ductal-carcinoma-in-situ, Paget’s disease, lobular carcinoma, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and also malignant phyllodes tumors in the literature (1, 5).

The association between hormonal therapy and malignancies is well-documented in biological women (6, 7), however the association of hormonal therapy with malignancies in transgender women is not as well understood. There is currently an increased theoretical risk of breast cancer in the transgender population based on the documented risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal biological women who take short-term combined progesterone and estrogen hormonal replacement therapy. There have been an increasing rate of reports of breast cancer in transgender women over the last few years (8, 9). However, a couple of large-scale studies in Europe have demonstrated that there was no increased risk of breast cancer in transgender women compared to biological women (8, 10). Similarly, in the United States a large retrospective medical record review of transgender veteran patients demonstrated that the incidence ratio of breast cancer in transgender women compared to that with biological women was 0.7, whereas it was 33.3 compared to biological males (9). It is important to note that only 3 out of 3566 transgender women patients in this study presented with breast cancer. However, they did present with late-stage disease that was not amenable to treatment and resulted in death which brings forth the importance of standard breast cancer screening recommendations in this population.

Screening Guideline:

Given the increased risk of breast cancer in this population relative to the average biological male patient it is prudent to include annual screening mammograms as a part of their overall health care. Recent studies in Europe have demonstrated the risk of breast cancer in transgender women increased during a relatively short duration of hormone treatment and the characteristics of the breast cancer resembled a more biological female pattern. This suggests that breast cancer screening guidelines for biological females are sufficient for transgender people using hormone treatment (11).

It is important to note that current screening guidelines vary according to the age of the individual and the duration of hormone therapy. In addition, lack of consensus among the organizations that provide recommendations for screening mammography for transgender women who are on hormone treatment, results in variable guidelines. An expert panel from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Center of Excellence for Transgender Health recommends biennial screening mammography starting at age 50 years for individuals who have taken hormone therapy for a minimum of 5 years. However in higher than average risk patients, it is recommended to reduce the age of onset of screening or increase the frequency of screening (12). This is in compare to Fenway Health (a large research organization dedicated to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health care in Boston, Massachusetts) who advocates annual screening mammography beginning at age 50 years in patients who have undergone a minimum of 5 years of hormone therapy (13).

The American College of Radiology Transgender Breast Cancer Screening (acr.org) guidelines (2021) are highlighted below (14):

Transfeminine (male-to-female) patient | ||

|---|---|---|

AGE: 40 years of age or older past or current hormone use ≥ 5 years. | Average-risk patient

| Digital breast tomosynthesis screening: May Be Appropriate Mammography screening: May Be Appropriate |

No hormone use (or hormone use less than 5 years) at any age | Average-risk patient

| No imaging modality is appropriate for screening

|

25 to 30 years of age or older past or current hormone use equal to or greater than 5 years

| Higher-than-average risk

| Digital breast tomosynthesis screening: Usually Appropriate Mammography screening: Usually Appropriate

|

25 to 30 years of age or older with no hormone use (or hormone use less than 5 years)

| Higher-than-average risk

| Digital breast tomosynthesis screening: May Be Appropriate Mammography screening: May Be Appropriate

|

Please refer to the for additional screening information including Transmasculine (female-to-male) screening guidelines.

References:

- Herman JL, Flores AR, O'Neill KK. How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States? June 2022.

- Parikh U, Mausner E, Chhor CM, Gao Y, Karrington I, Heller SL. Breast Imaging in Transgender Patients: What the Radiologist Should Know. Radiographics. 2020 Jan-Feb;40(1):13-27. . Epub 2019 Nov 29. PMID: 31782932.

- Weyers S, Villeirs G, Vanherreweghe E, Verstraelen H, Monstrey S, Van den Broecke R, Gerris J. Mammography and Breast Sonography in Transsexual Women. Eur J Radiol. 2010 Jun;74(3):508-13. . Epub 2009 Apr 9. PMID: 19359116.

- Berliere M, Coche M, Lacroix C, Riggi J, Coyette M, Coulie J, Galant C, Fellah L, Leconte I, Maiter D, Duhoux FP, François A. Effects of Hormones on Breast Development and Breast Cancer Risk in Transgender Women. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Dec 30;15(1):245. . PMID: 36612241; PMCID: PMC9818520.

- Patel H, Arruarana V, Yao L, Cui X, Ray E. Effects of Hormones and Hormone Therapy on Breast Tissue in Transgender Patients: A Concise Review. Endocrine. 2020 Apr;68(1):6-15. . Epub 2020 Feb 17. PMID: 32067157; PMCID: PMC7252590.

- Chen CL, Weiss NS, Newcomb P, Barlow W, White E. Hormone Replacement Therapy in Relation to Breast Cancer. JAMA. 2002 Feb 13;287(6):734-41. . PMID: 11851540.

- Gooren LJ, van Trotsenburg MA, Giltay EJ, van Diest PJ. Breast Cancer Development in Transsexual Subjects Receiving Cross-sex Hormone Treatment. J Sex Med. 2013 Dec;10(12):3129-34. . Epub 2013 Sep 9. PMID: 24010586.

- Gooren L, Bowers M, Lips P, Konings IR. Five New Cases of Breast Cancer in Transsexual Persons. Andrologia. 2015 Dec;47(10):1202-5. . Epub 2015 Jan 22. PMID: 25611459.

- Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of Breast Cancer in a Cohort of 5,135 Transgender Veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015 Jan;149(1):191-8. . Epub 2014 Nov 27. PMID: 25428790.

- Gooren LJ, van Trotsenburg MA, Giltay EJ, van Diest PJ. Breast Cancer Development in Transsexual Subjects Receiving Cross-sex Hormone Treatment. J Sex Med. 2013 Dec;10(12):3129-34. . Epub 2013 Sep 9. PMID: 24010586.

- De Blok CJM, Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, van Engelen K, Adank MA, Dreijerink KMA, Barbé E, Konings IRHM, den Heijer M. Breast Cancer Risk in Transgender People Receiving Hormone Treatment: Nationwide Cohort Study in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2019 May 14;365:l1652. . PMID: 31088823; PMCID: PMC6515308.

- Deutsch MB. Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People. 2nd edition. . Accessed 2/20/2024.

- Makadon HJ, Mayer KH, Potter J, Goldhammer H. Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: American College of Physicians, 2015.

- Brown A, Lourenco A P, Neill B L, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Transgender Breast Cancer Screening. Available at . American College of Radiology. Accessed 1/10/2024.